Should you give a flux about flux analysis?

Why analytics are so important

Data surrounds accountants – invoices, collections, bills, payrolls, etc. – and the challenge every month, quarter and year-end is transforming that data into useful information so we can confidently guide decision makers. Having confidence in our results isn’t always easy, because we are trying to synthesize so much information, so quickly.

How then do we bridge the complex and ever-expanding universe of accounting data with being able to communicate clearly both a detailed substantiation of the data and a deep understanding of the why behind the numbers? The answer is analytics. Analytics give us a methodical way to view and interpret large data sets and is becoming an increasingly important month-end control.

Flux analysis is one of the most popular analytic procedures for good reason as it enables teams to accomplish multiple objectives concurrently: communicating why changes occurred requires examining what has and has not occurred over time. In seeking answers, we exercise control over the accounting data and address the risks that activity is improperly recorded. In the end, both what happened and why is understood.

Treat flux analysis as both a review and substantiation workflow

In deciding to implement a flux analysis, you may have a specific goal – implementing additional controls for your month-end close; substantiating year end balances; answering the questions of your management team. These goals are not mutually exclusive.

As a review procedure, flux analysis provides a window into identifying errors and needed changes to the financial statements. With this exercise, we are trying to drill-into the details to understand if there have been any transactions that may have been booked incorrectly, missed accruals, or other changes that still need to be made to the financials to close the books. Flux analysis also provides an opportunity for managers to be engaged in the details by reviewing the prepared analysis.

As an analytical procedure, flux analysis is a substantiation process that complements the work that’s already been done to close the ledger accounts. Even though flux analysis doesn’t prove out account balances, flux analysis is an excellent internal control procedure for companies to ensure that – at a high-level – accounts do not have unexplained or unsubstantiated material changes from prior periods and that any material changes are verified and understood. Flux analysis is not a substitute for reconciliation; in this exercise we’re striving to answer “why” instead of “what”.

As a reporting procedure, flux reports are often used to inform others of changes in the business. Because a flux analysis typically sets boundaries for what requires explanation, reporting out the results becomes a great opportunity to call attention to only the most relevant activity. Given that non-accounting stakeholders often want higher-level information or specific-cuts of the data, individual account explanations can be used to inform and roll up into aggregate FSLI or account grouping commentary.

Drive from the what to the why

Providing flux explanations can take a lot of time. Every accountant is used to the mundane steps it takes to prepare a flux explanation, going into the ledger, exporting and running pivots tables, finding a missing accrual or miscoded transaction, adjusting the transaction(s), and re-exporting. Finally, you are ready to get to the actual goal - providing the explanation and leaving rich context for others to understand what has occurred.

If the first portion has taken too long, then the quality of explanations invariably suffers. It is therefore critical that teams focus on building detailed close processes so team members can dedicate sufficient time to providing quality explanations.

Keep the reporting simple and iterate

There are a few considerations to keep in mind when selecting the level-of detail to run a flux process. Natural ledger accounts are typically a good starting place to build from, as using highly aggregated level such as the financial statement line items detracts from the ability to catch errors, since aggregation combines offsetting mistakes. Using a high level of disaggregation such as dimensions alongside accounts not only creates a lot more work from a volume perspective but also creates situations where numerous account-dimension combinations have the same explanations as others or fall below thresholds to even require investigation.

Materiality thresholds are also critical in building a strong flux process, but can also be tricky to get right. High materiality thresholds will cause small errors to go undetected, and lower thresholds may ultimately create too much work with preparers being forced to explain variances that are operationally immaterial. When setting the precision of the flux analysis, aligning dollar thresholds with materiality guidelines used by auditors is beneficial. 1% of pre-tax income, 0.25% of revenue, or 0.1% of assets are all commonly used. Using both percentage and fixed dollar criteria is also important in order to filter out normal operating fluctuations.

When in doubt, collaborate with your auditors about what they would like to see, use common sense and don’t over complicate, and iterate. If you routinely are having too many accounts flagged for reasons that are not meaningful to the business, adjust the thresholds and build more nuanced rules.

Understanding expectations

Building a best in-class flux process requires not just explaining what is observed, but also comparing it to what was expected to happen. Consider a liability account for a material deferred tax payment; in most months the account balance will be unchanged, and when considering fixed dollar and percentage variance thresholds, this liability account will not be identified for explanation. However, in the month the liability is due, the absence of an account variance actually indicates an error, that the payment was incorrectly recorded or even not made. An expectation of a variance on the account alerts the preparer or reviewer of the error when the variance is not observed.

From this example one can see that addressing the absence of what's expected is as equally important as explaining the unexpected. Implementing expectations into your flux analysis doesn’t require major changes to documentation, simply shifting one's mindset in the exercise of preparing or reviewing is enough. Asking “what do I expect to see?” takes a step back from the rigidity that arises in analytics and leads to a more thoughtful control exercise.

Key take-aways

A flux analysis is a simple-to-implement analytical procedure that engages multiple team members and offers operational and control benefits for companies of all sizes, especially companies subject to audits or other reporting accountabilities. Implementation decisions like the level of account detail and precision thresholds are important, and common practices taken from the auditing profession may guide these choices. Setting expectations, while not an intuitive exercise, is a critical practice for maximizing the analysis’s value, and a questioning mindset is one way to get there.

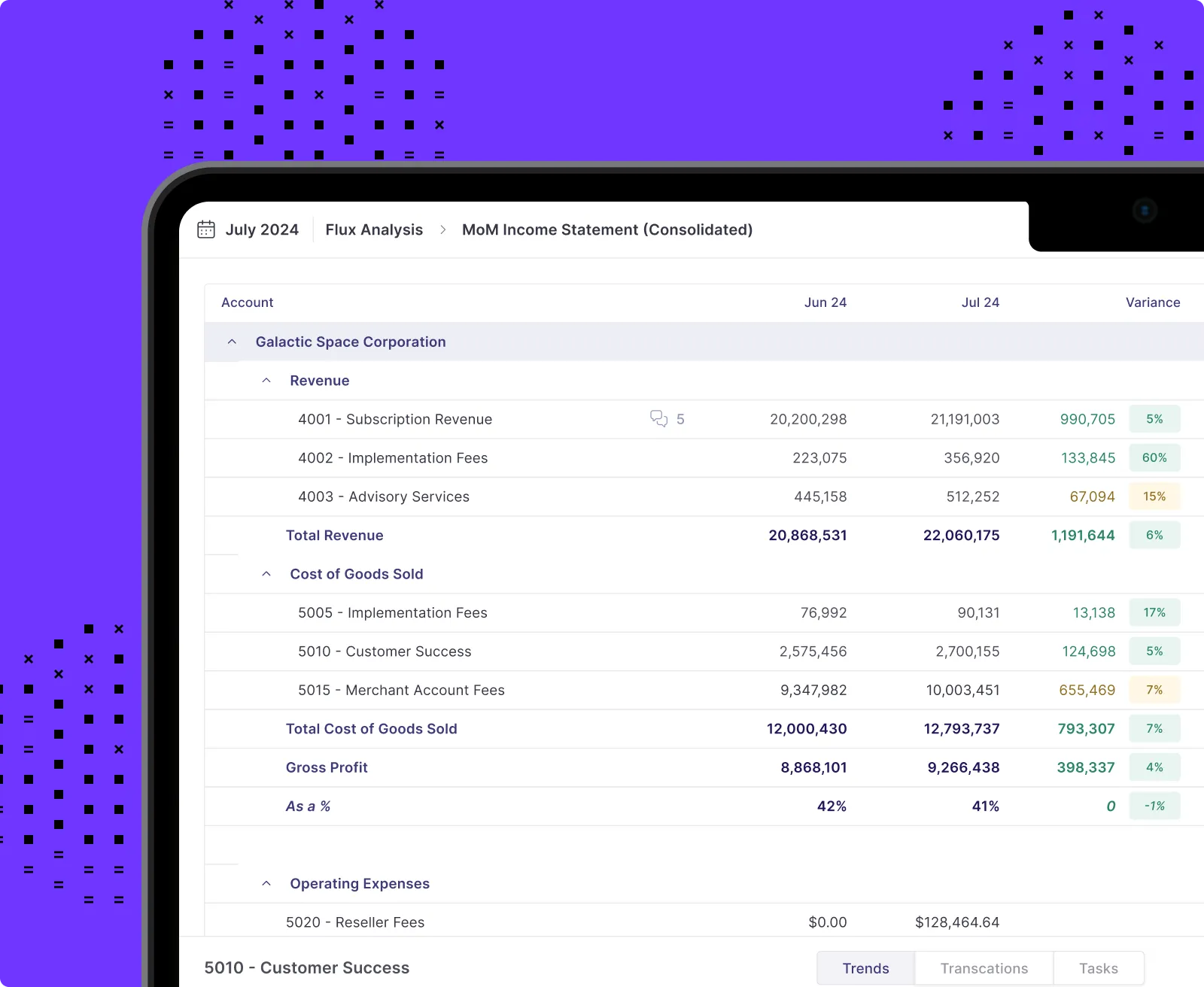

Check out Numeric for how to run a better flux

With modern tools like Numeric, a flux analysis is easier than ever and can make a noticeable difference in the quality of your next accounting close.

Numeric gives teams a single pane of glass to not only see where explanations are required, but to pull up ledger details, run pivots by vendor, department, and more, so 100% of the team’s time can be focused on the WHY! From my firsthand experience using Numeric Flux, it is one of those rare aha moments where you sit back and say, “damn, I’ve been waiting years for someone to build a flux report like this.” It is fast to pull up all the details I need, quick to refresh financial data, and clear about the responsibilities of everyone on the team.

.png)

.png)

.png)